What if you never get your morning flat white again?

With the coffee and dairy industries in peril due to climate change, that could become a reality, affecting the livelihoods of more than 1.25 billion people worldwide.

Photo: Anay Mridul

2018/19 is projected to be the biggest year for coffee production ever. But 60% of wild coffee species are under the risk of extinction, including coffea arabica, which amounts for about 60% of the total coffee grown globally. “The consumer is not seeing the threat currently,” says Henry Clifford, a coffee exporter at DRWakefield, “since prices are low due to the massive glut in production.”

Jean Zuluaga, Head of Imports for the Organisation of Spanish Coffee Producers, explains how crops are affected. “If we overproduce in the soil, we have to stabilise it. If we don’t give anything back to the soil, how are we going to recover it?”

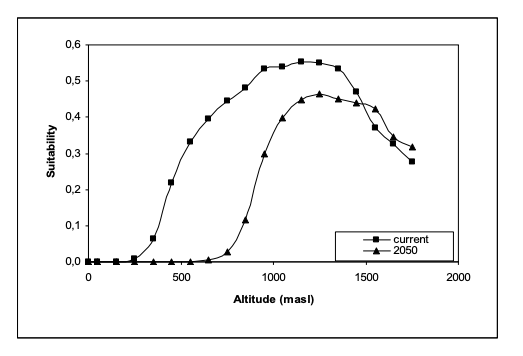

The relation between current and future (2050) coffee suitability and altitude of coffee (coffea arabica). Figure: Laderach et al (2011)

He says importers have to look farther away to bring coffees in because of the rise in temperatures. “We see a lot of plagues in the coffees we receive, and we have to decline them because we can’t work with those types of coffees.”

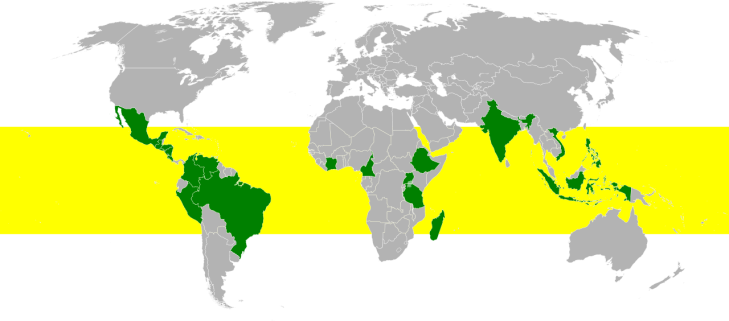

Zuluaga’s brother is one of the 25 million coffee farmers whose subsistence can be disrupted by climate change. Without stringent action, the global area suitable for growing coffee could be cut by half by 2050. This will result in the global coffee belt expanding away from the Tropics. Zuluaga repents this, branding coffee production as a means of survival for farmers. “It’s not a business, it’s their livelihood.”

The top 20 producing countries, lying on the global coffee belt. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Fairtrade revealed that arabica production will rise 300m to 500m higher above sea level by 2050 to mitigate losses. Here, Clifford breaks down the phenomenon:

The coffee industry has close ties with the dairy sector, which is home to around 1.8 million cows in the UK. But extreme weather conditions have taken a toll on their production capacities. Heat stress is a critical issue, according to Ed Towers, a dairy farmer at Lune Valley’s Brades Farm. “The perfect temperature for a cow is between 14°C and minus 10°C, because they have trouble bearing heat.” This is why heat waves like last year’s are detrimental to the production of milk.

Dairy cows. Photo: Farm Watch/CC

Extreme weather conditions affect their daily work. “Your weather window is either massive, and nothing’s growing because it’s too dry,” says Towers, “or tiny because it’s too wet and there’s only a couple of days of dry weather.”

Towers is a strong advocate of animal agriculture, especially with the needs of the growing global population. He sees it as “taking foods that are not nutritious enough or are undigestible for humans, and turning them into the highest digestible stuff fit for human consumption.”

He believes that climate change will have a greater effect on the non-dairy sector. Alternative milks have been on the rise for a long time now; oat and almond milks had a fourfold year-on-year growth in 2018. It’s a prerequisite for every coffee shop to offer plant-based milks.

We don’t add sugar to our oat drink, but we do add some vitamins like A, D, riboflavin, B12 and calcium to keep things modern and cool for everyone–especially our vegan friends living rad plant-based lives. pic.twitter.com/eDllCSk6hG

— OatlyUK (@OatlyUK) February 19, 2019

“There is a lot of land you can’t grow crops on. Crops like oats can’t move to areas that are more favourable for growth, whereas a dairy farmer can buy food from other farms to feed the cows,” explains Towers. “If there is desertification or drought, then crop farms can’t actually produce anything.”

He commends vegans for their efforts in changing buying habits. “That’s consumers using their money to drive a change,” he says. “The enemies are the people who don’t care and buy just the cheapest product.”

But the system won’t work if everyone turns vegan. For example, once oats they are milked, they’re then fed to cows. As ruminants, they digest byproducts unfit for human consumption, and turn it into high-quality, nutritious milk. “That’s why we need both animal and non-animal agriculture systems, otherwise, it doesn’t work,” reiterates Towers. “Pulling a piece out breaks the puzzle.”

Addressing the glass bottle solution, Towers explains, “There’s the carbon cost of producing, recycling and reusing it, which is the climate side of it. But if the product doesn’t break down ever, it’s a big pollution problem.” The CO2 cost for glass is higher than plastic, and it needs to be washed and reused at least seven times to be more sustainable than two-litre bottles.

Glass milk bottles aren’t the best solution, according to Towers. Photo: Wes Schaeffer/CC

Many economies depend on coffee export, and climate change presents a major challenge. “If supply decreases, who will support all the over costs?” Zuluaga asks, irate. “The coffee we drink in Europe depends on those poor third-world countries that produce it as a means of survival.”

Bodies like the National Federation of Coffee Growers in Colombia and ANACAFE in Guatemala have taken measures to facilitate producers. “They provide a model of sustainability and how to combat this,” says Clifford. “It would be good if more countries, created bodies like that.”

“Apart from climate and carbon taxes, costs need to be more linked to the carbon and methane costs of production,” argues Towers. “The products that are actually bad for the environment are going to cost a lot and be less economic.”